RON OGAN

I was born on August 1, 1931, in Marshalltown, Iowa and attended rural schools in Marshall and Poweshiek counties through eighth grade. I graduated from Montezuma High School in 1948 and became a farmer and truck driver from 1948 to 1952. In that year, I knew my draft number was coming up and it wasn't wise to put in a crop, so I volunteered for military service. I was inducted into the U.S. Army in June 1952. At that time, this was a fairly normal experience for young people my age. It was a duty we knew we would be called to respond to. I wasn't anxious for it, but I felt I was qualified to serve, and could help protect our country and our people, providing a safe place for my family and friends to live. I received my basic training at Fort Riley, Kansas, and completed it in December of '52. I was sent home for a 30 day furlough over Christmas, prior to shipping out of San Francisco, California in January 1953, bound for Japan.

During the ship ride from San Francisco to Tokyo, I spent the first two days being seasick and unable to eat. It turned out to be fortunate that I was required to be on guard duty at night, because I had to pass through the kitchen. Twice each night, I was invited by the kitchen staff to eat my meal there, and it was much better food than the mess hall.

Upon arrival at Japan, we were transported by train to a formal Japanese officer training camp. It was a lovely facility that looked like a vacation spot. We had good accommodations, and this is where I spent two months in school, being trained in CBR (chemical, biological, and radiological) warfare, which was how to treat myself and others if we were attacked.

We were nowhere near Hiroshima, and it was years after the atom bomb had been dropped in 1945. I spent one afternoon in Tokyo, but I didn't have the opportunity to see other parts of the country. I saw only a small portion of the city - that which was adjacent to the army base. I wasn't particularly impressed although I am sure it was typical of the country. I could understand that because of some of the problems that had taken place there. People were friendly, not expecting a lot out of life, but trying to make the best of it. From what I saw, they seemed to have pretty good transportation for people to get about. There were fast moving trains, maybe not by today's standards, but there were many buses. They used many U.S. ex-military vehicles, which were partially destroyed in the war, re-manufactured in Japan, and used by local residents for other purposes. I think they had done as good a job for their citizens as the country was able to do.

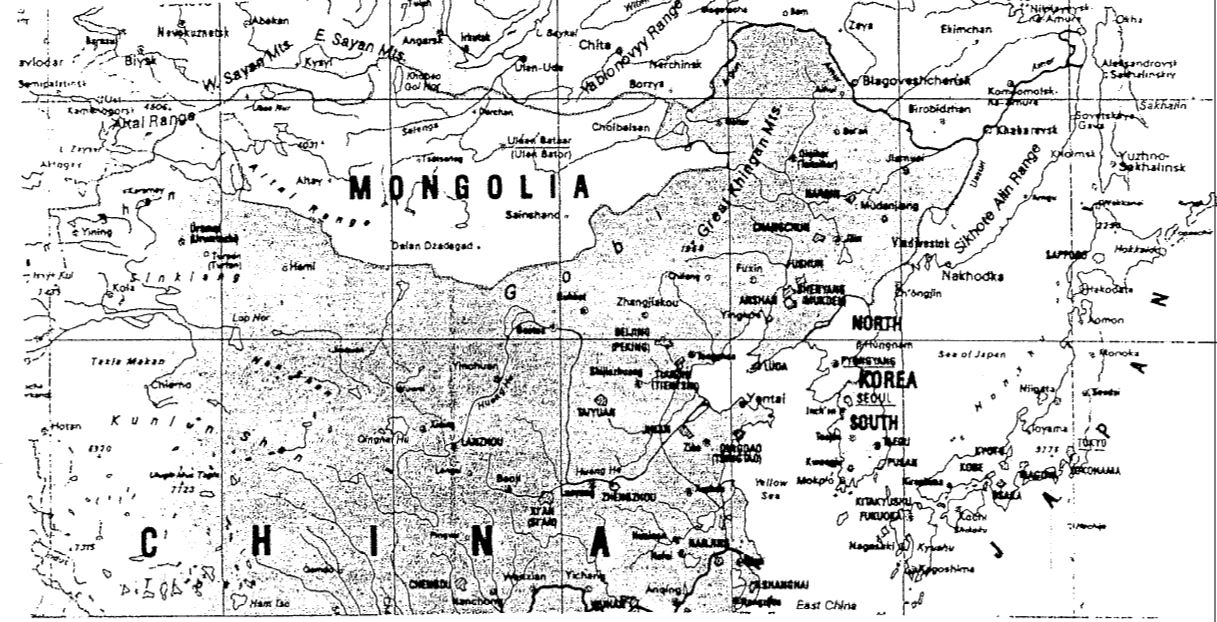

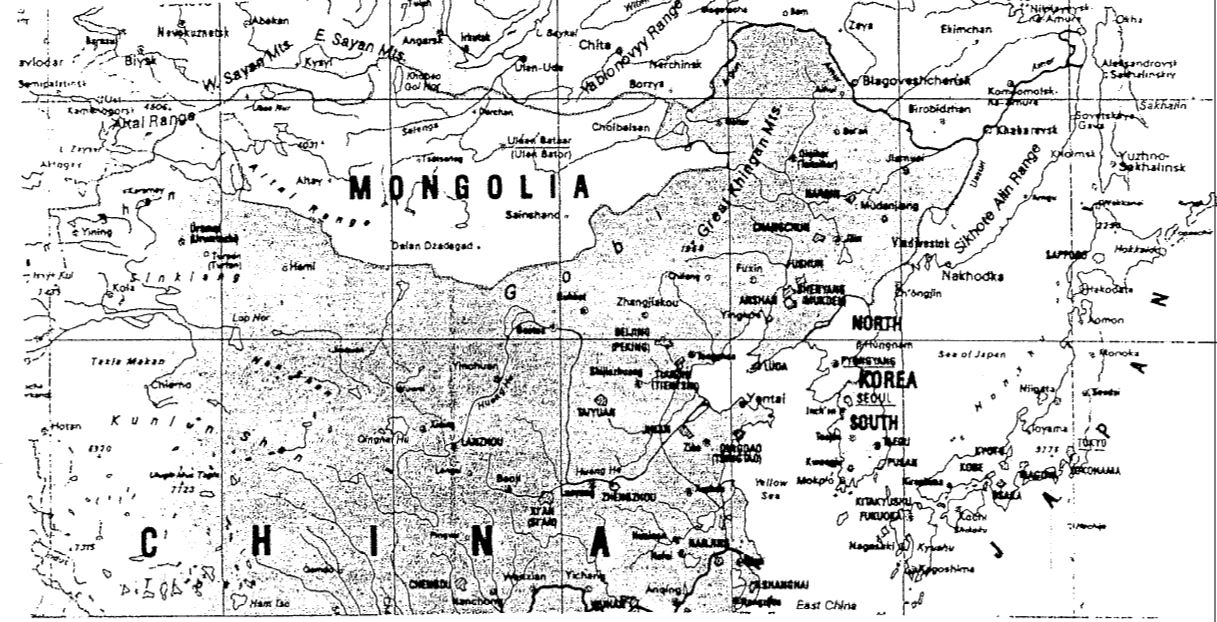

After the schooling was completed, we were ordered to be shipped to Korea in March, 1953. However, I was sidetracked, spending two months in a hospital in Japan after an appendectomy. When I was released, I was shipped on to Korea in May 1953. We flew in a plane that was much like a box-car which hauled trucks, jeeps, equipment, and personnel. There were sling seats that folded down from the side-walls. It was not bad and a very short trip.

After we arrived from Japan, we proceeded to the front lines after a 20 mile overnight hike in the rain and were stationed with the Fox Company Infantry Division. I was greeted by 53 letters from family and friends in the United States. These were the first messages I had received since I left the States in January.

I served as mortar weapons man in the mortar platoon, later became the mortar platoon sergeant, and then the leader. While on active duty on line, the demilitarized zone was declared, giving us an almost non-combat situation.

In October '53, I was relocated to the Second Regimental Headquarters of the Second Infantry Division in Korea. Headquarters' duties were principally clerk typist, office machine operator, truck driver, and jeep driver for a 2nd Lieutenant in the headquarters office, who was also a friend. In addition, I was calisthenics leader for our headquarters' platoon non commissioned soldiers. This was probably the mildest winter I have ever experienced, which was fortunate because we lived in 24-man tents. I picked up another duty, being regarded as chief heating stove operator during the winter months.

Almost everything in Korea was crude. I was only in the northern part, close to the demilitarized zone, which separated North from South Korea. I was never in the cities, and it may have been different there, but what I saw was very war torn. Most buildings were temporary, and the terrain was like I would imagine the desert to be - sandy soil, mountainous, hilly, and mostly sage brush. There was very little farming as we would think of it. There were rice paddies on the mountains. A farmer's rice paddy might not be bigger than an Osceola city lot. Their homes were in a village.

Where I was, there were no sanitary facilities. We bathed in the river. We didn't have running water, so we transported water to the kitchens to make coffee and to provide drinking water. When I was in regimental headquarters, we rigged up a shower. We used timber from destroyed buildings to make a platform. On it we put a metal barrel about seven feet in the air. Each day we would collect water from a stream, put it in the barrel, and let the sun heat it. We'd open a spigot on the barrel and take a shower. As time went on, we improved on it. We rigged up a sand box underneath it where we could put oil to light, and warm the water even more. We also went up the mountain a ways with a rubber hose, laid it in the stream, put a rock on it and let the water run through the hose into our barrel. Even though it wouldn't compare to home, we finally had good shower facilities.

At Regimental Headquarters we had six commanding officers - the Commander and five people under him. Our Regimental Commander was a Colonel in the Army. He had a shower rigged up on a two-wheel trailer, about 8x12 feet with a little building constructed on it. There was a tank where water was heated, and he even had an attendant who cleaned the shower daily, filled the water barrel, and heated the water so the officer could have his shower each day.

Even though there were not to be any firearms, there were some. We were situated in a river valley, and off to our right was a hill, like a mound of dirt, that was blasted every night. It was impossible to dig trenches because the dirt was all broken up until it was like loose sand. However, we didn't come in contact with casualties during my term of serving on the Demilitarized Zone. Every person who served in our company had to go on patrol at least once. As the radioman, when we went out on patrol I walked at the head of our group with our squad leader who was a 1st Lieutenant. We followed radio communication wires along the paths, probably a foot deep. Every time the patrol went out, they strung a wire from our company out as far as we went, and fortunately we had no casualties, which we were very concerned about. However, at a certain point we discovered our path had been crossed by the enemy, and that automatically meant we weren't to go any farther. We stayed there until time to retreat.

The only casualty I came into contact with was one person from another company who had been on patrol the night before. I was with a group that went out to take him back to our line. He was put into a Red Cross ambulance and taken to a hospital. However, he was already dead when we picked him up. We did have an experience one night when mortars were dropped into our "ammo" dump, and there were a lot of explosions, but no casualties. We went out one night to pick up two prisoners to take to division headquarters. They were classified as casualties but were alive.

I departed Korea for the U.S. in April 1954, arriving in San Francisco by ship and being greeted by thousands of people. This included an aunt and uncle, who were vacationing there that week. They were invited to eat the evening meal on base. Later that same night I boarded a plane for Colorado Springs, Colorado, and was relieved of active duty with the U.S. Army. I boarded a train, headed for Grinnell, Iowa where I was greeted by my parents for a long stay in Iowa. I have resided here ever since.

I drove a truck for a year, and then I took a job in Des Moines, servicing office equipment. After nine years, I owned and operated an office equipment business in Osceola for 23 years. On October 10, 1959, I married the most wonderful lady, Virginia Johnson, and we have enjoyed 45 years together. In December 1959, we moved to Osceola where we still reside, raising two great children. Mark arrived on October 10, 1960, and Mindy on May 2, 1966. From 1989 to 2002, I was employed by the Des Moines Public Schools as a service technician. During 10 of those years, I drove a commuter bus from Osceola to Des Moines and back, transporting workers from Osceola to Des Moines for the day and returning them home. A full story of our family is in Volume 5 of Recipes for Living.

I am now enjoying semi-retirement. I work part-time at Pamida, and I have a number of hobbies: gardening, carpentry, lawn care, visiting restored barns publicized by the Iowa Barn Foundation. Another hobby I have picked up is visiting lighthouses and collecting miniature models of the ones I've seen. I discovered there are lots of them - 60-some around Lake Michigan, which a visitor can see on a self-guided tour. Also I collect miniature 1 to 32nd scale tractors of the ones I'd driven as a teenager and a young farmer.

Life is good for our family. We are grateful for the freedom that we and other Americans enjoy as a result of sacrifices made by hundreds of thousands of men and women who served our country in the military.

We pray that future generations may live in a world where war, terrorism, hatred, and fear are unknown.

Return to main page for Recipes for Living 2005 by Fern Underwood

Last Revised March 13, 2013